The northern royal albatross colony at Taiaroa Head has been used to estimate the birds’ survival rates at different ages in a single model. The new estimate by Dragonfly updates the survival rate calculation from 1993, which was based on re-sighting data from 1937–1993.

Since then, a number of things have changed – climate and marine conditions, population size and the distribution of fishing effort – and better analysis methods are available.

The northern royal albatross colony at Taiaroa Head has been used to estimate the birds’ survival rates at different ages in a single model. The new estimate by Dragonfly Science updates the survival rate calculation from 1993, which was based on re-sighting data from 1937–1993.

Since then, a number of things have changed – climate and marine conditions, population size and the distribution of fishing effort – and better analysis methods are available.

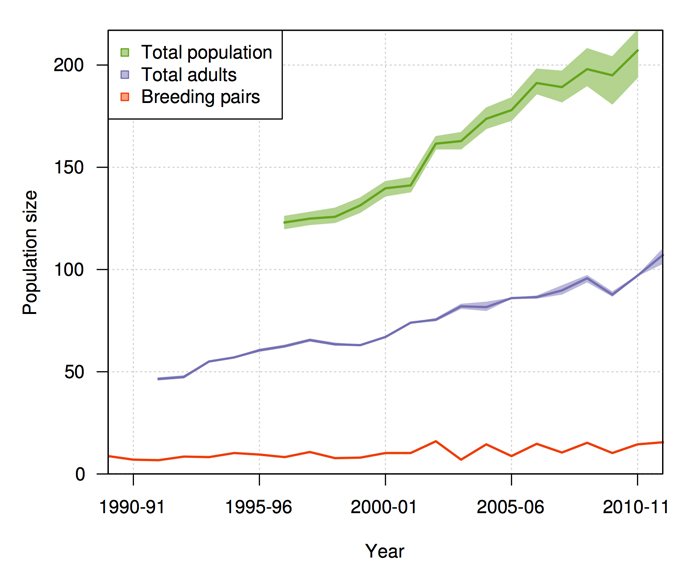

Yvan, who carried out the analysis, estimated the number of juveniles, pre-breeders and breeding pairs in each age range and calculated the ratio of the number of breeding pairs and the number of adults, to the total population. This ratio is thought to be the only direct estimate available for biennially breeding albatross. Survival rates agreed with previous estimates.

“This mainland colony is great because it’s been followed from the beginning. Since 1938, when a few birds came over from the Chathams and started to breed there, every bird has been banded and monitored, which is unique given the seabirds’ usual habit of breeding in remote, inaccessible places,” he says.

The colony is only 5% of the total population of northern royals, with the remainder breeding on small islands near the Chatham Islands. At Taiaroa Head, the colony is actively managed, mainly by providing intensive predator control and egg and chick fostering programmes. It is a popular tourist attraction and educational facility.

Despite an excellent data set, Yvan says the analysis, using a single Bayesian multi-state capture-recapture model, was challenging.

“It’s quite complex because you’re never going to see every bird each year – they spend much of their juvenile years at sea and also breed every second year. So, if you see an individual one year but not the following year, you don’t know if they are dead or not – it might just be their year off. To cope with this, we had to model the probability of seeing them separately from the survival rate.”

“It’s quite complex because you’re never going to see every bird each year – they spend much of their juvenile years at sea and also breed every second year. So, if you see an individual one year but not the following year, you don’t know if they are dead or not – it might just be their year off. To cope with this, we had to model the probability of seeing them separately from the survival rate.”

The results have established the northern royals as a sentinel albatross population, from which population data from other species can be compared. He says important lessons can be drawn from Dragonfly’s analysis.

“We found quite a big variation in the number of breeding pairs in different years. A bad winter, such as in 2000, can set off a pattern of synchronised breeding so nearly all the birds are breeding in the same alternate years. If you just took a snapshot of the colony, you could mistakenly think the population was either doing extremely well or very poorly, depending on the year.

Northern royal albatross were recently identified as one of the seabird species most at risk from incidental captures in commercial fisheries in New Zealand. It is estimated that around 100 birds from the total population (from the Chathams and from Taiaroa Head) are killed each year in fishing related-activities.

“This new estimate shows that the number of birds lost to bycatch is not increasing. Despite the losses, the future is promising and Taiaroa Head will remain a very important data set for further biological studies.”